A Visual Guide to Concurrency Control

Today, parallel execution is almost a default requirement for blockchains that want to increase throughput, optimize transaction costs, and reduce latency. It is no longer fashionable to design a blockchain that executes transactions sequentially (like Ethereum and other first-generation blockchains), especially with recent hardware improvements favoring parallelism.

Rialo implements parallel execution for faster and cheaper transactions. However, when implementing parallel execution systems, we have to answer an important question: How do we process many transactions in parallel while making sure execution produces correct results? The sequential execution model is slow but always correct – it makes sense to adopt another approach to executing transactions only if it guarantees the same level of correctness.

Concurrency control is how chains that implement parallel execution maintain correctness and preserve safety. Different chains adopt varying approaches to concurrency control, and this decision – although oblivious to users and developers – has a tangible impact on how a chain performs and affects the user experience in many ways.

Transactions failing repeatedly for no reason? Users seeing long delays in execution? Chain performance slowing down whenever onchain activity is high? These are often signs that a chain is running into the limits of concurrency control and experiencing the tradeoffs of parallel execution. But, without understanding the basics of parallel execution, it can be hard for anyone who’s not a protocol researcher to recognize and understand these issues.

We’ve built a dashboard to visualize concurrency control that you can access at https://concurrency-control.learn.rialo.io/ It shows you various approaches to concurrency control–and by extension, parallel execution–illustrates the tradeoffs of each approach. You can play around with this demo to observe how parallel execution behaves under different conditions. In this blog post, we’ll provide a useful overview of parallel execution, concurrency control, and everything else you need to understand to take full advantage of the visualizer.

Parallel vs. sequential execution: A brief introduction

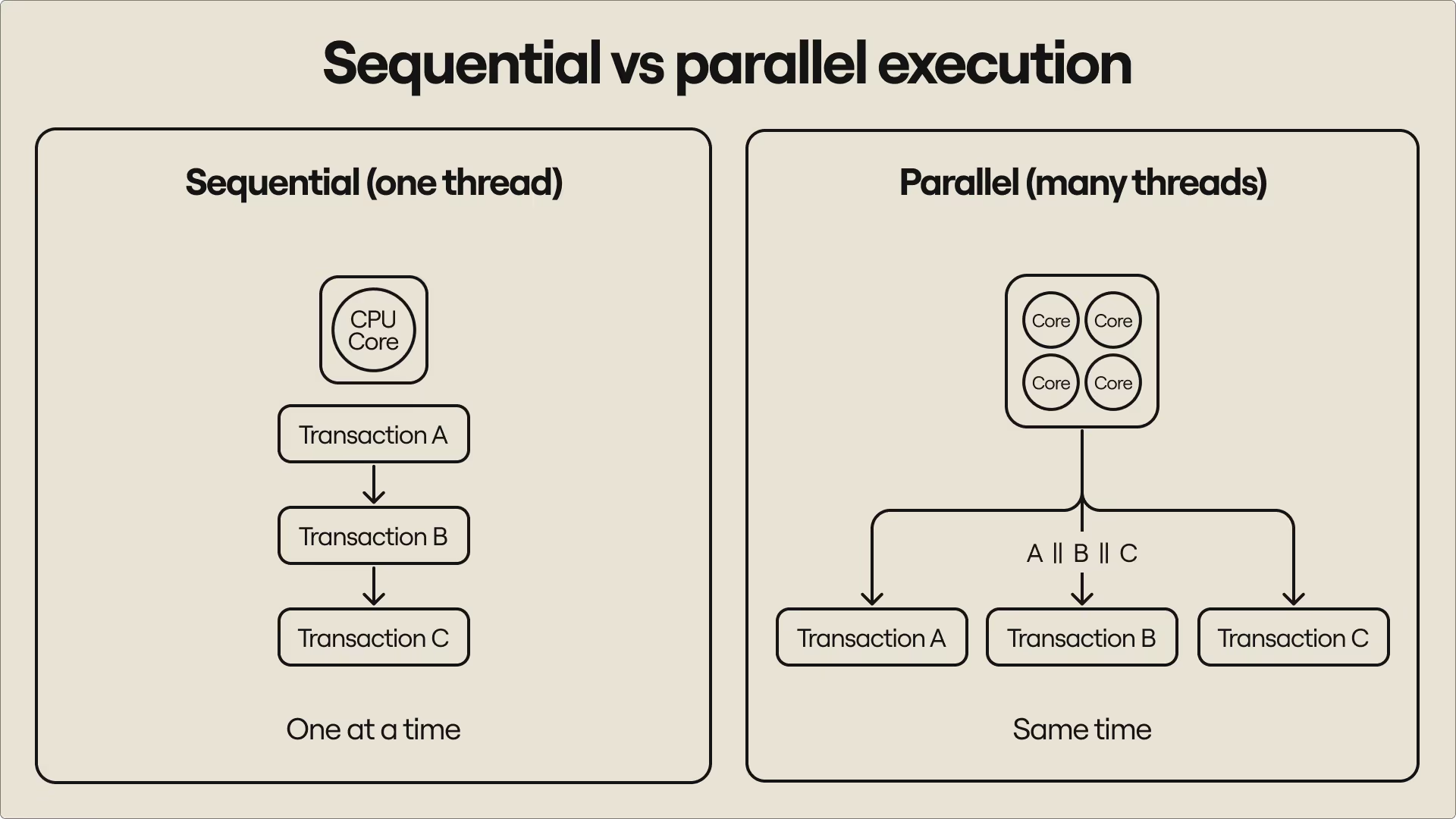

To use a blockchain, you must submit transactions. A transaction instructs the chain to do something: send tokens, check an account’s balance, call a smart contract, or create a new address. The blockchain can process transactions sequentially or concurrently (i.e., in parallel). Sequential execution requires executing transactions one after the other, often in their order of arrival. Parallel execution executes multiple transactions at the same time without forcing transactions to wait.

Sequential execution preserves correctness, but often artificially limits throughput; execution must follow a single thread and cannot take advantage of newer CPU designs that distribute work across multiple threads for faster performance (parallelism). Parallel execution improves performance by spreading the work of processing transactions across multiple threads on the same machine–cores on a CPU, if you will–but it introduces conflicts that make execution produce incorrect outcomes.

We’ll illustrate the problem with a quick example:

Imagine an account has a balance of $100. Two transactions (A and B) arrive at the same time with different instructions targeting the same account:

- Transaction A subtracts $30

- Transaction B adds $50

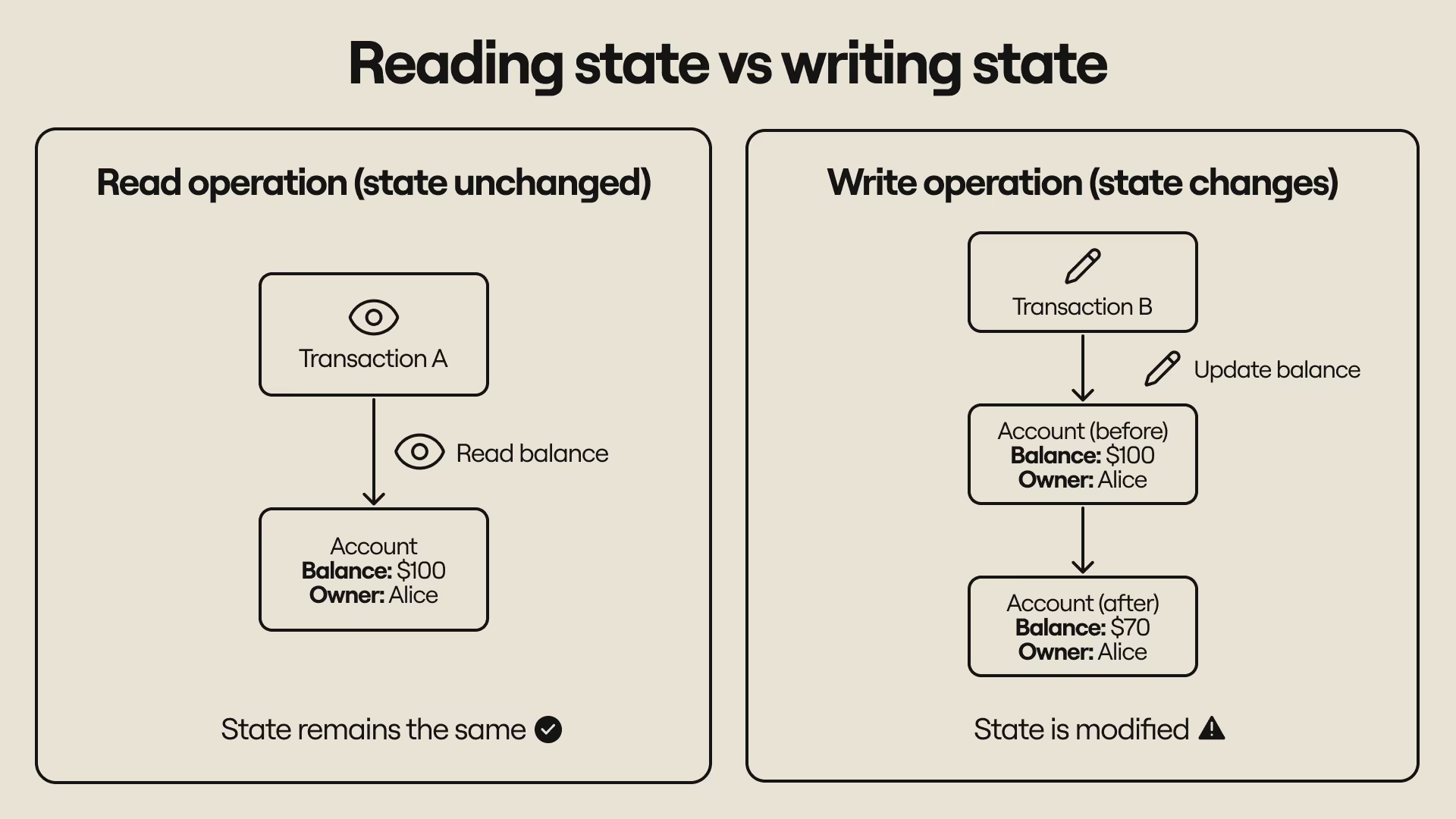

Each transaction needs to: (a) Check the account balance, (b) Update the balance after executing. Checking the account balance is a read operation and doesn’t change the account’s state. Updating the account balance is a write operation and changes the account’s state.

“State” is the snapshot of an account at a point in time, or, simply, what we “know” about the account at that point. It includes things like an account’s (current) owner and total balance–the $100 balance is part of the account’s state in this example. By reducing or increasing the balance, we have changed the state (merely checking the balance doesn’t alter the state).

The transactions execute differently under sequential and parallel execution modes:

Sequential execution (safe)

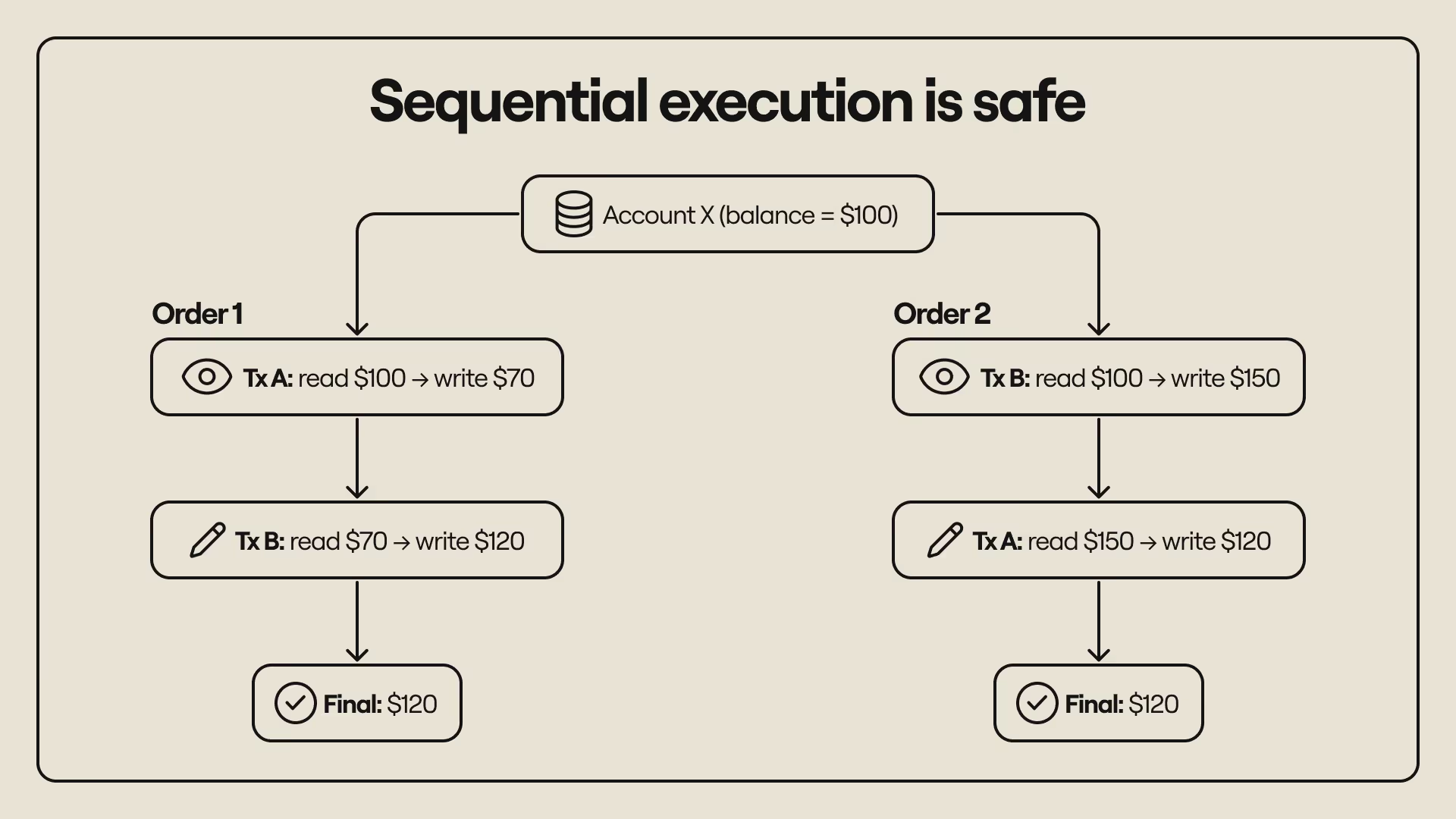

Transactions are executed one after the other. Transaction A might execute before B: It reads the balance ($100), subtracts $30, and updates the balance to $70. Transaction B reads the balance ($70), adds $50, and writes $120 as the new balance. Or transaction B might execute before transaction A: it reads the balance ($100), adds $50, and updates the balance to $150. Transaction A reads the current balance ($150), subtracts $30, and writes $120 as the new balance.

No matter the order of execution, the final result is always $120. We’ll see why this property is important and why it’s hard to enforce when parallel execution is used instead of sequential execution.

Parallel execution (naive example)

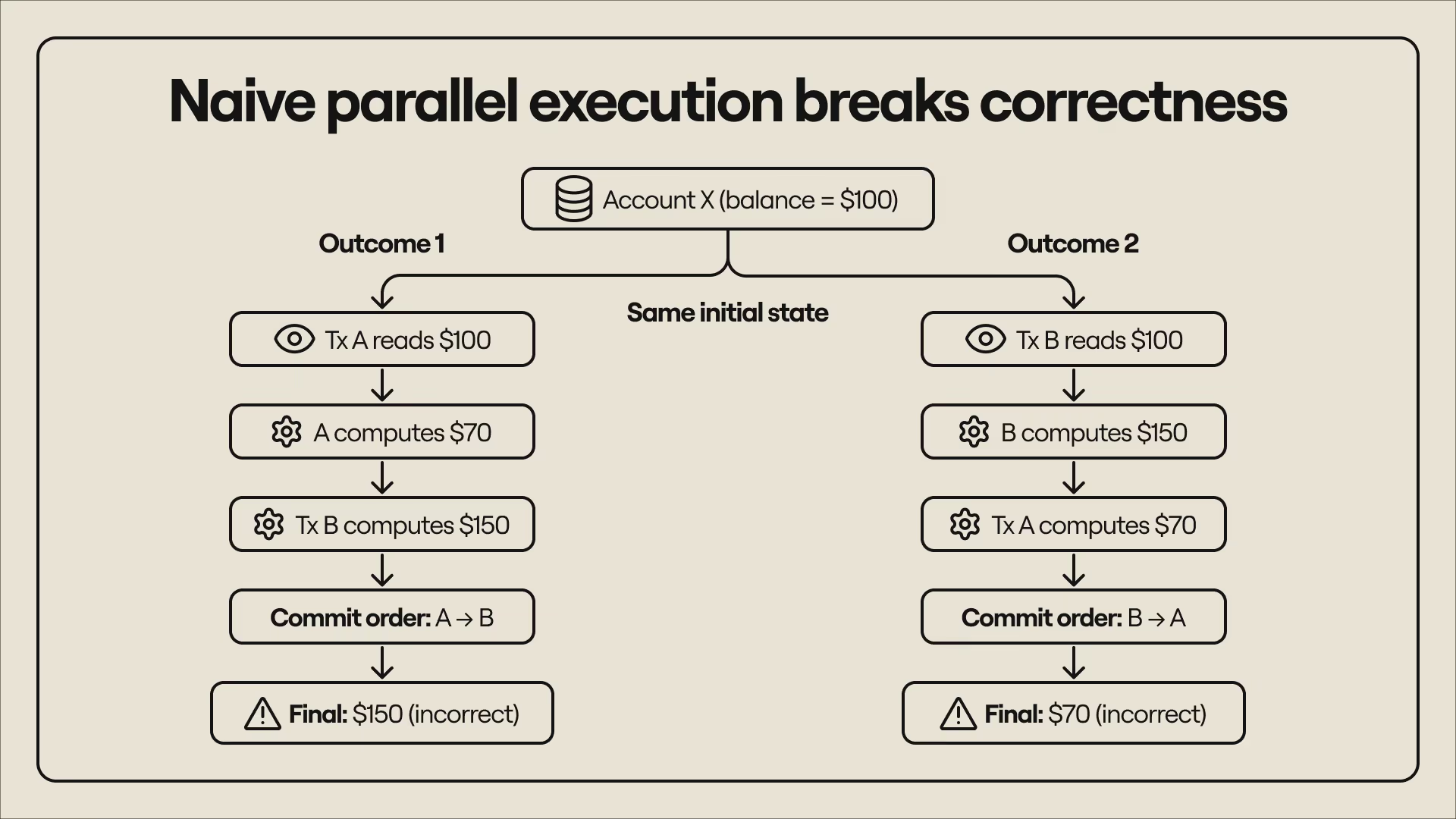

Transactions are executed concurrently, but commits (i.e., writing new states) are ordered–the state committed by the last transaction takes precedence over states committed by earlier transactions. The transactions, A and B, start together and both read an initial balance of $100. Here’s what happens depending on how and when the transactions update the account state:

- Transaction A computes $100 - $30 and commits $70. Transaction B simultaneously computes $100 + $50 and later commits $150, overwriting the old value and leaving $150 as the final balance.

- Transaction B computes $100 + $50 and commits $150. Transaction A simultaneously computes $100 - $30 and later commits $70, overwriting the old value and leaving the final balance as $70.

Both scenarios result in incorrect updates to the account’s balance. The first (final balance: $150) prints additional money, while the second (final balance: $70) destroys money. More importantly, the results are not the same as those we got by executing the transactions in strict sequential order. This violates an important property of parallel execution–that the outcome of concurrently executing a set of transactions cannot be different from the outcome of sequentially executing the same transactions.

This is where conflicts enter the picture.

Handling conflicts in parallel execution

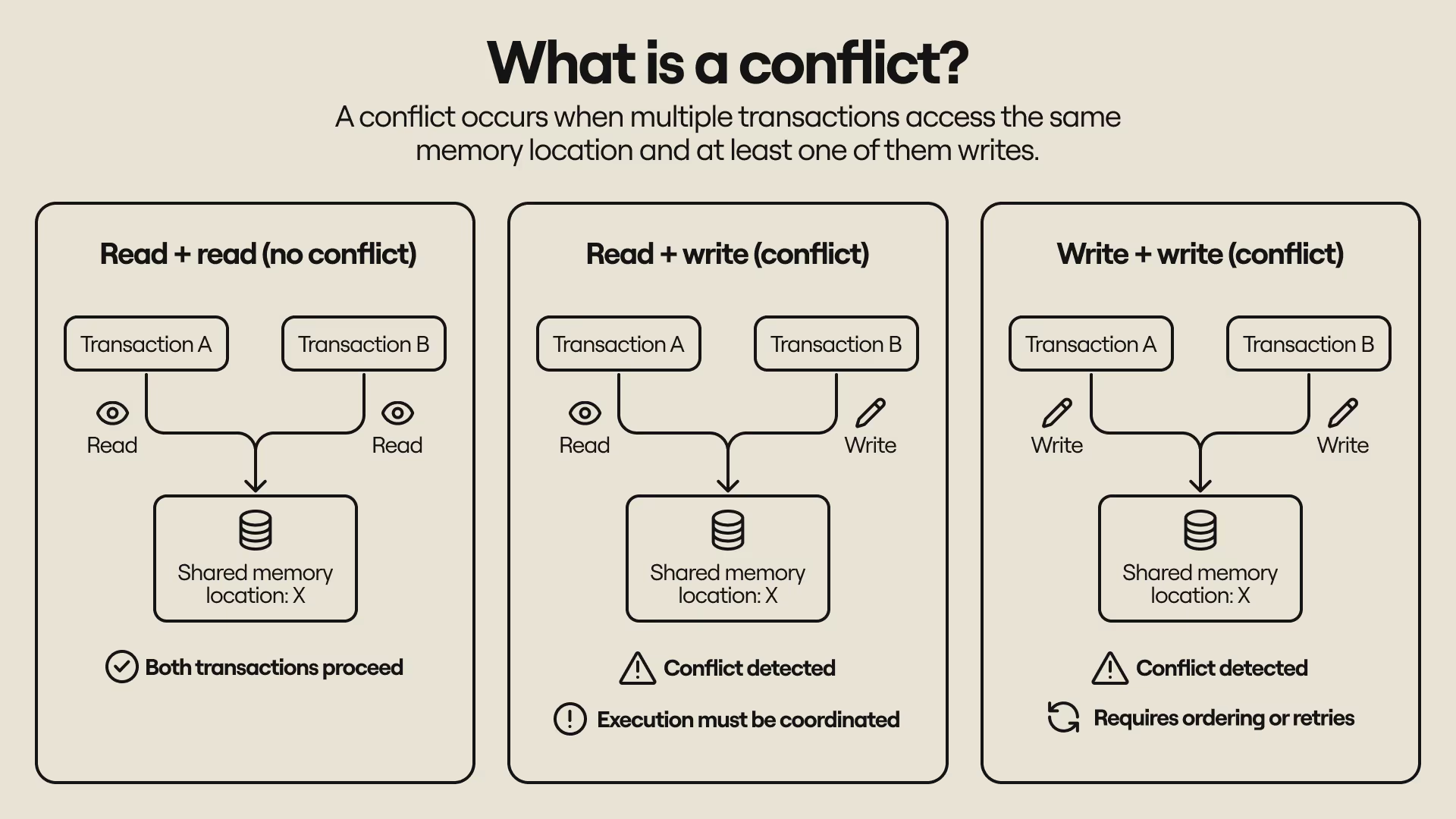

The problem in the second example is that the two transactions access the same account, and each one tries to update the state as soon as execution completes. It creates what we call a conflict. A conflict occurs when two transactions touch the same account, and the correctness of execution depends on when transactions accessed the (shared) state.

The naive parallel execution example produced incorrect results because the transactions read state (checked the balance) at the same time, but wrote state (changed the balance) at different times. Of course, this is the system working as intended–parallel execution usually allows multiple transactions to simultaneously read an account state but restricts updates to account state to one transaction at a time. However, this arrangement creates issues for safe execution.

If two transactions can read the same initial state, but one transaction changes the state while the other transaction is still processing, the old state–and any results based on it–becomes invalid. In the first parallel execution scenario, Transaction A and Transaction B both read $100 as the initial balance, but Transaction A updated the balance to $70. Transaction B executed the operation with the old balance ($100), which caused it to update the account balance with the wrong result ($150).

In the second scenario, Transaction A and Transaction B read $100 as the initial balance, but Transaction B updated the balance to $150 while Transaction A was still processing. Transaction A executed the old state ($100), which led to it updating the account balance with the wrong value ($70). In both cases, a transaction was executed with stale data and published an update that did not match the account’s latest state or reflect the outcome of serially executing the transactions.

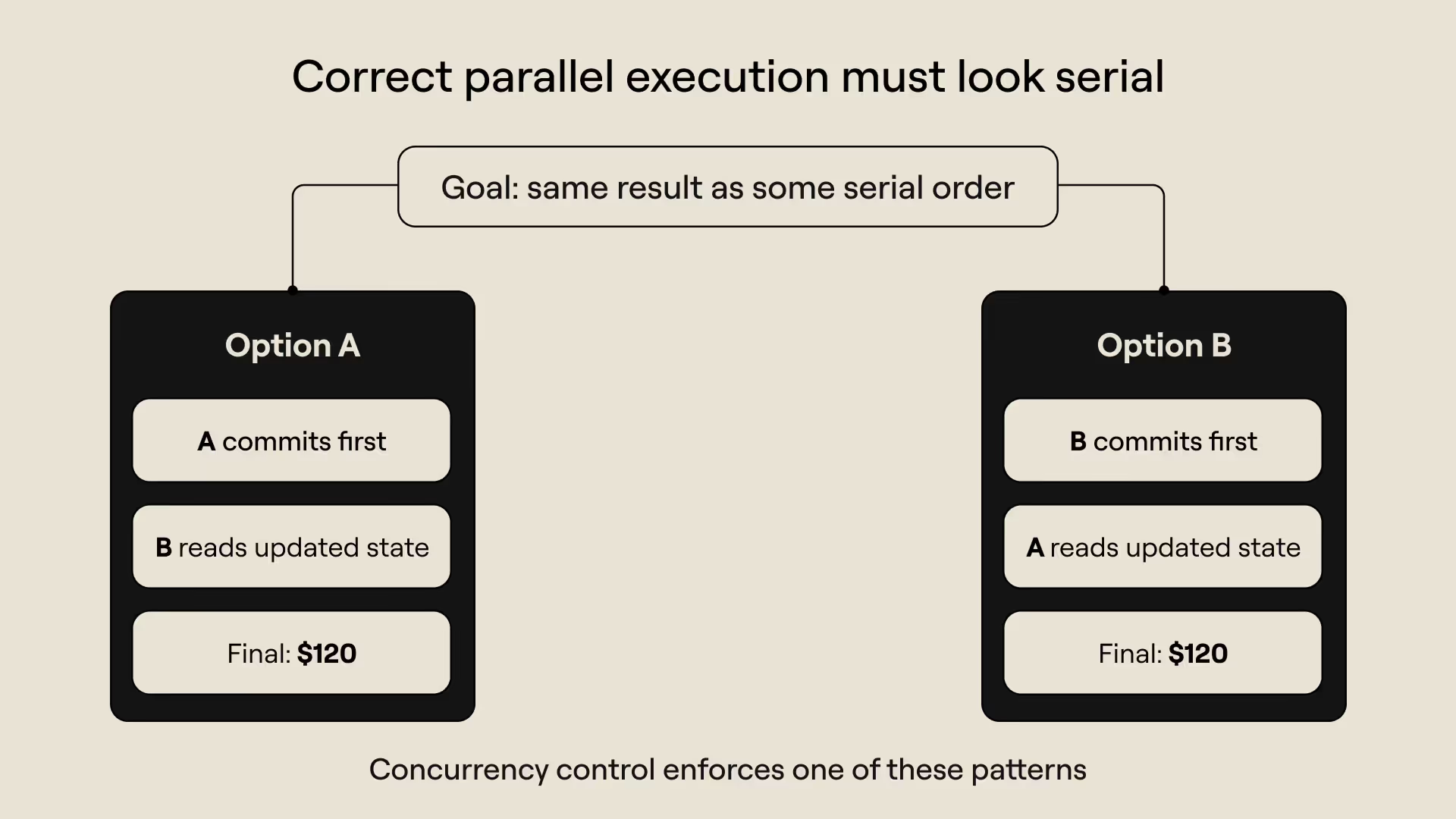

The problem could be solved if we revised state access to reflect transaction conflicts and changed the execution ordering to prevent transactions from reading and executing based on stale data. The ideal transaction order would be like this:

- Transaction A reads the account balance and commits a new value before Transaction B reads and writes the same account, or

- Transaction B reads the account balance and commits a new value before Transaction A reads and writes the account

This new execution pattern produces the correct results. In the first scenario, Transaction A reads $100 as the balance and writes back $70; Transaction B reads $70 as the balance and writes $120 as the new balance. In the second scenario, Transaction B reads $100 as the balance and writes back $150; Transaction A reads the new balance ($150) and writes $120 as the final balance.

You’ll notice that the result of executing the transactions now looks like they were executed sequentially. In fact, the transactions are executed sequentially in this example. This is where concurrency control really enters the picture–what we did in this example (enforcing sequential access to state for both reads and writes) is one way of managing conflicts that could impact the correctness of parallel execution. We’ll explore two approaches to concurrency control in the next section.

Pessimistic execution vs. optimistic execution

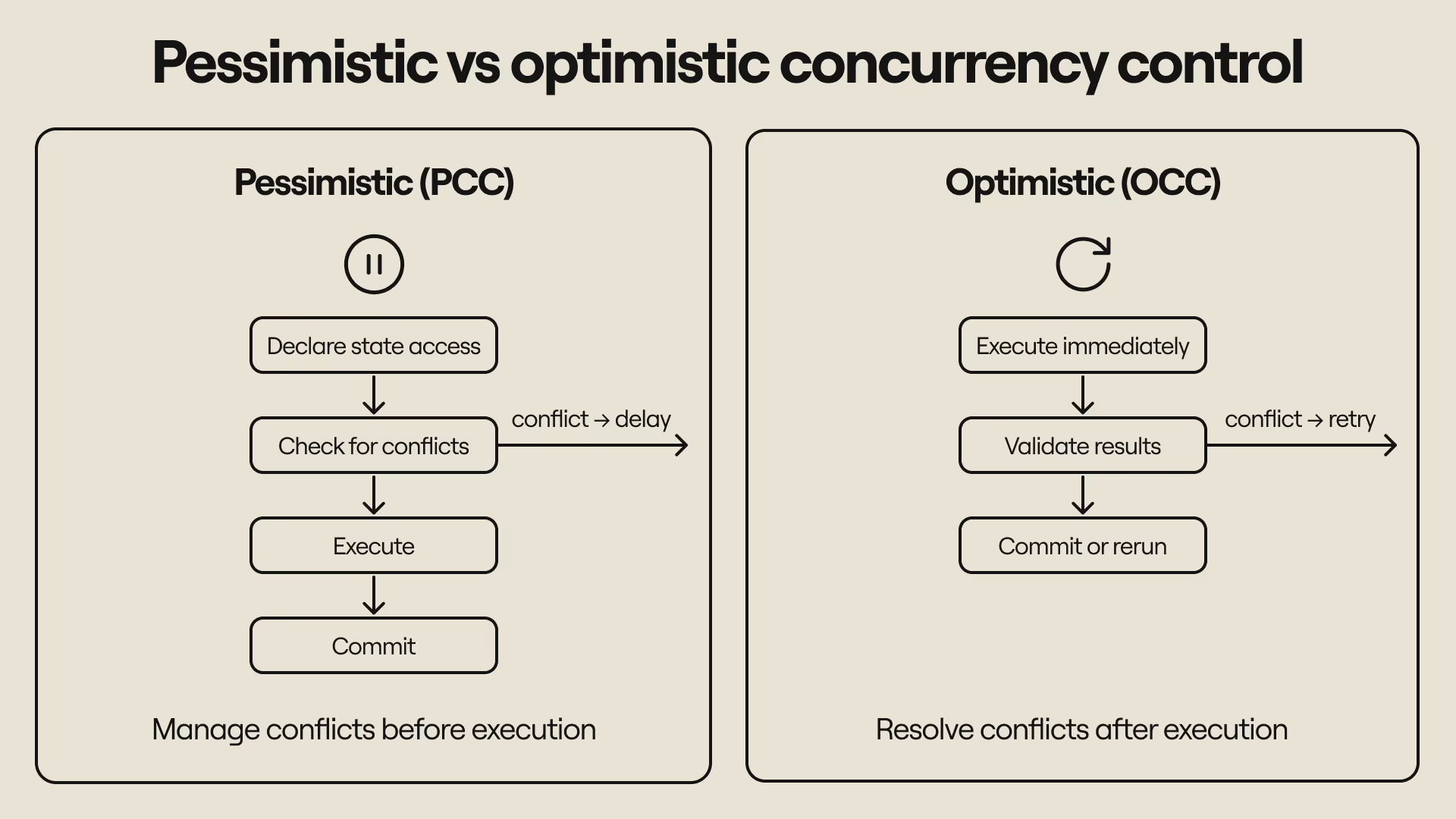

There are two primary approaches to concurrency control: pessimistic concurrency control (PCC) and optimistic concurrency control (OCC). We’ll use “pessimistic execution” and “optimistic execution” for simplicity (the visualization similarly uses simpler names, such as Pessimistic Mode for pessimistic concurrency control and Optimistic Mode for optimistic concurrency control). Both are techniques for preserving correctness during parallel execution and making sure that they satisfy the serializability constraint.

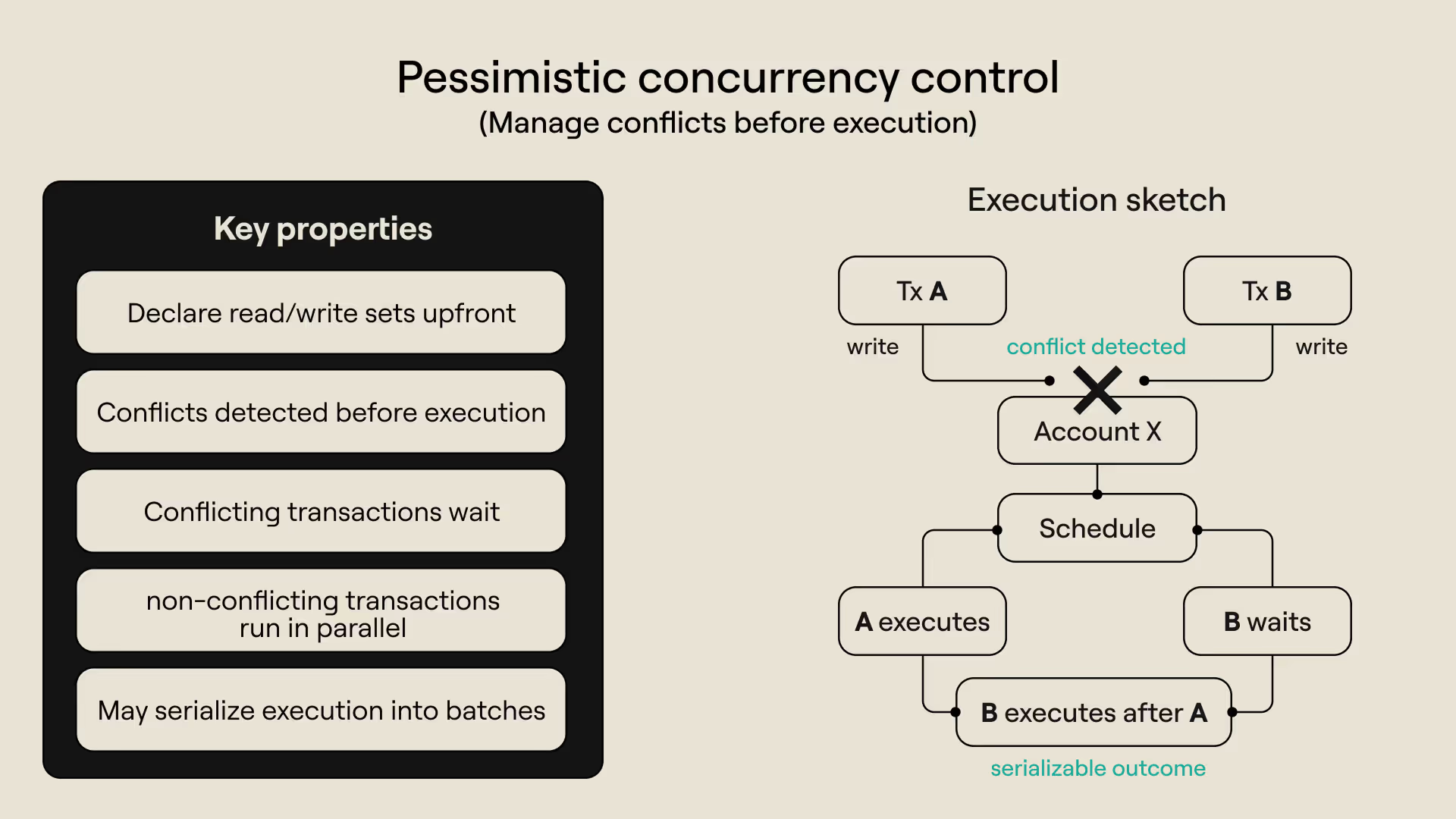

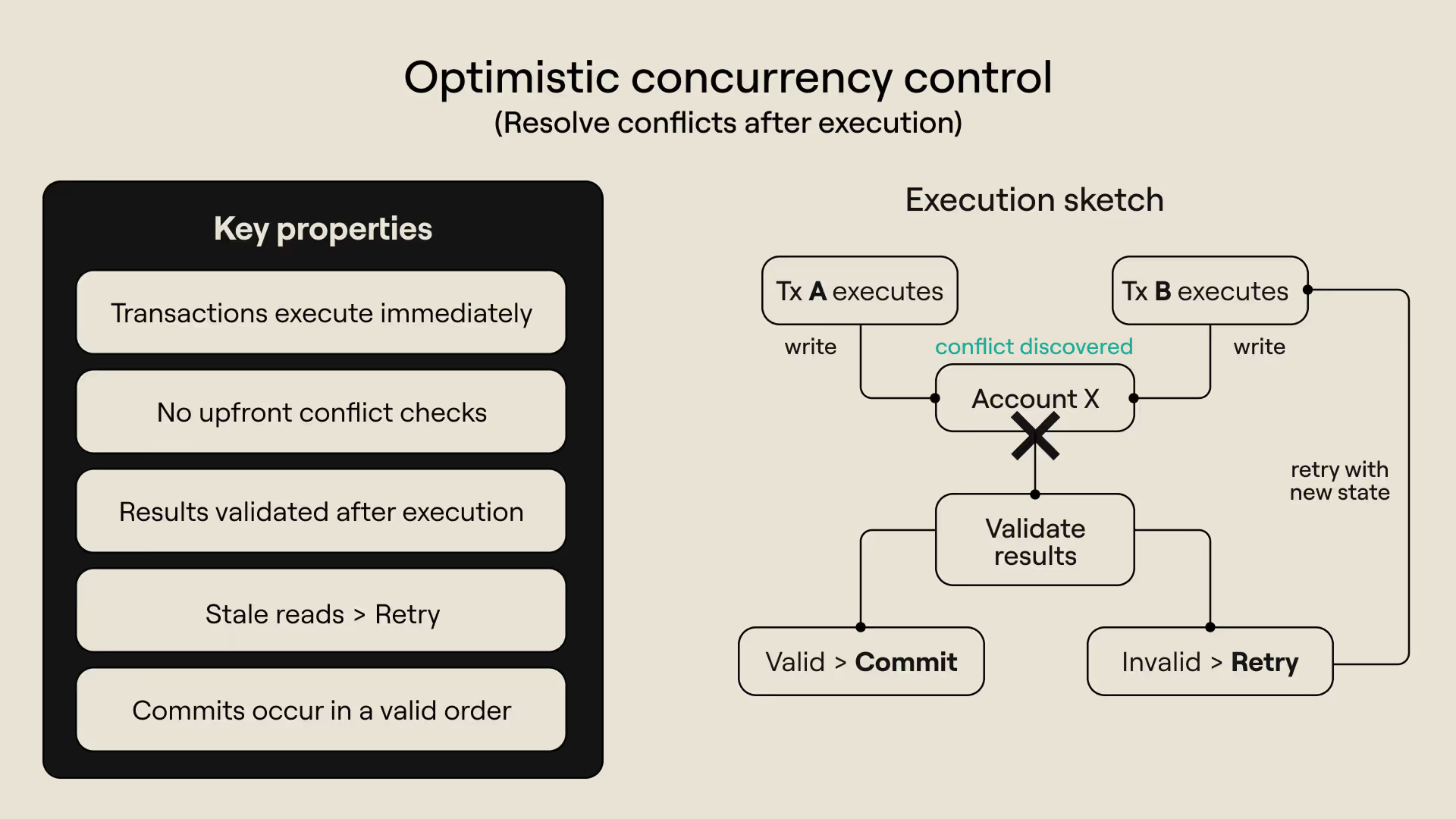

Pessimistic concurrency control and optimistic concurrency control manage conflicts differently. Pessimistic systems manage conflicts upfront and try to prevent them before execution. Optimistic systems allow execution to proceed without delay and try to resolve conflicts after execution.

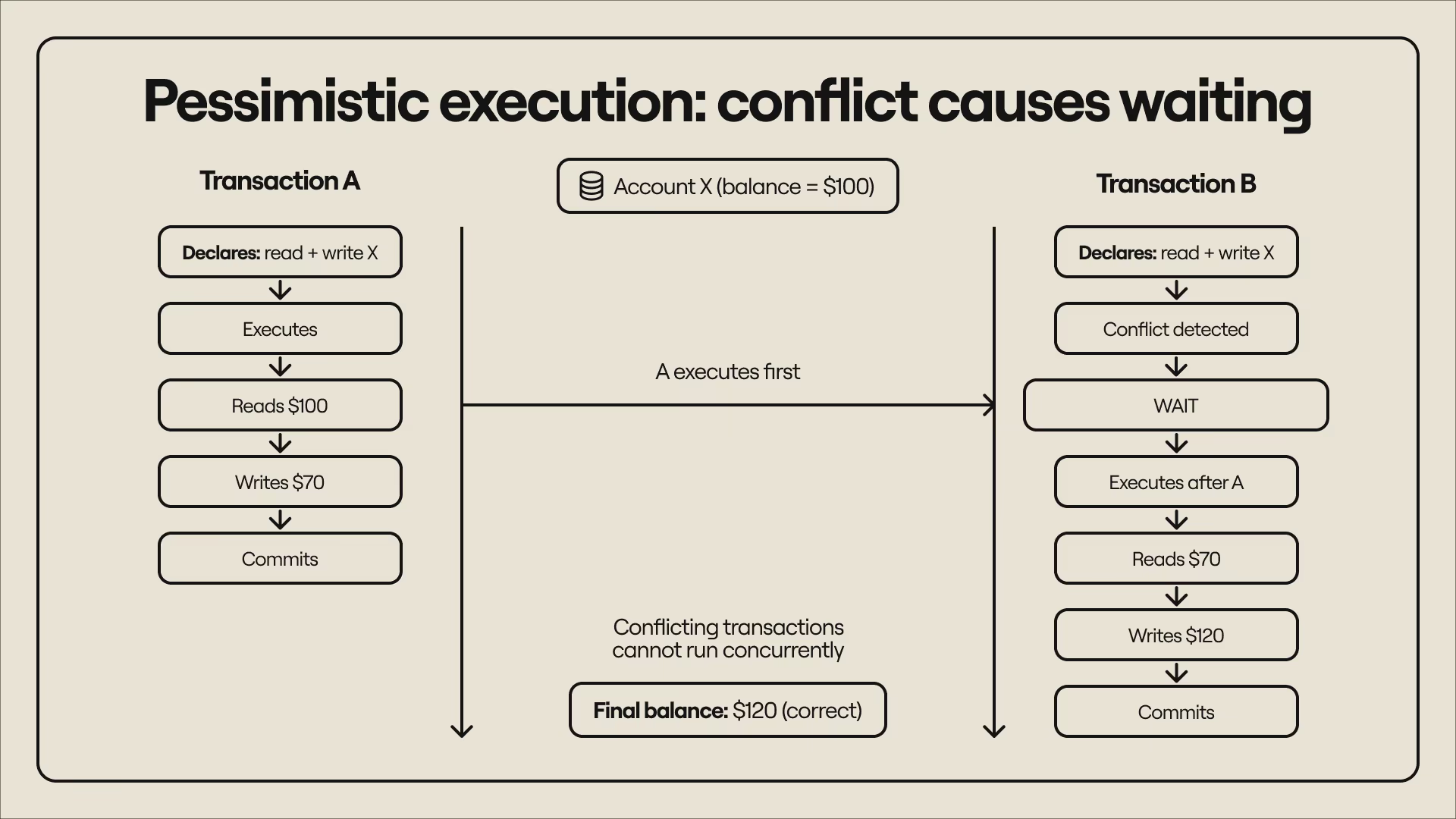

The result is always the same, but both systems pay the cost of uncertainty (the uncertainty of not knowing if transactions will conflict) differently. Pessimistic execution systems pay this cost upfront (before execution) in the form of delays–a transaction might be delayed if its execution could conflict with another transaction. To reason about potential conflicts, pessimistic execution requires transactions to declare what accounts they touch and whether they’re reading state or writing state (or both), and uses that information to schedule execution. To use a previous example:

- Transaction A and Transaction B both declare that they will read and write to the same account. This creates a conflict and means the transactions cannot execute concurrently. Either transaction can go first as long as execution is sequential.

- Transaction A goes first, reading an initial balance of $100 and writing a new balance of $70. Transaction B later reads a balance of $70 and writes a new balance of $120 ($70 + $30).

- Transaction B goes first, reading an initial balance of $100 and writing a new balance of $150. Transaction A later reads a balance of $150 and writes a new balance of $120 ($150 - $30).

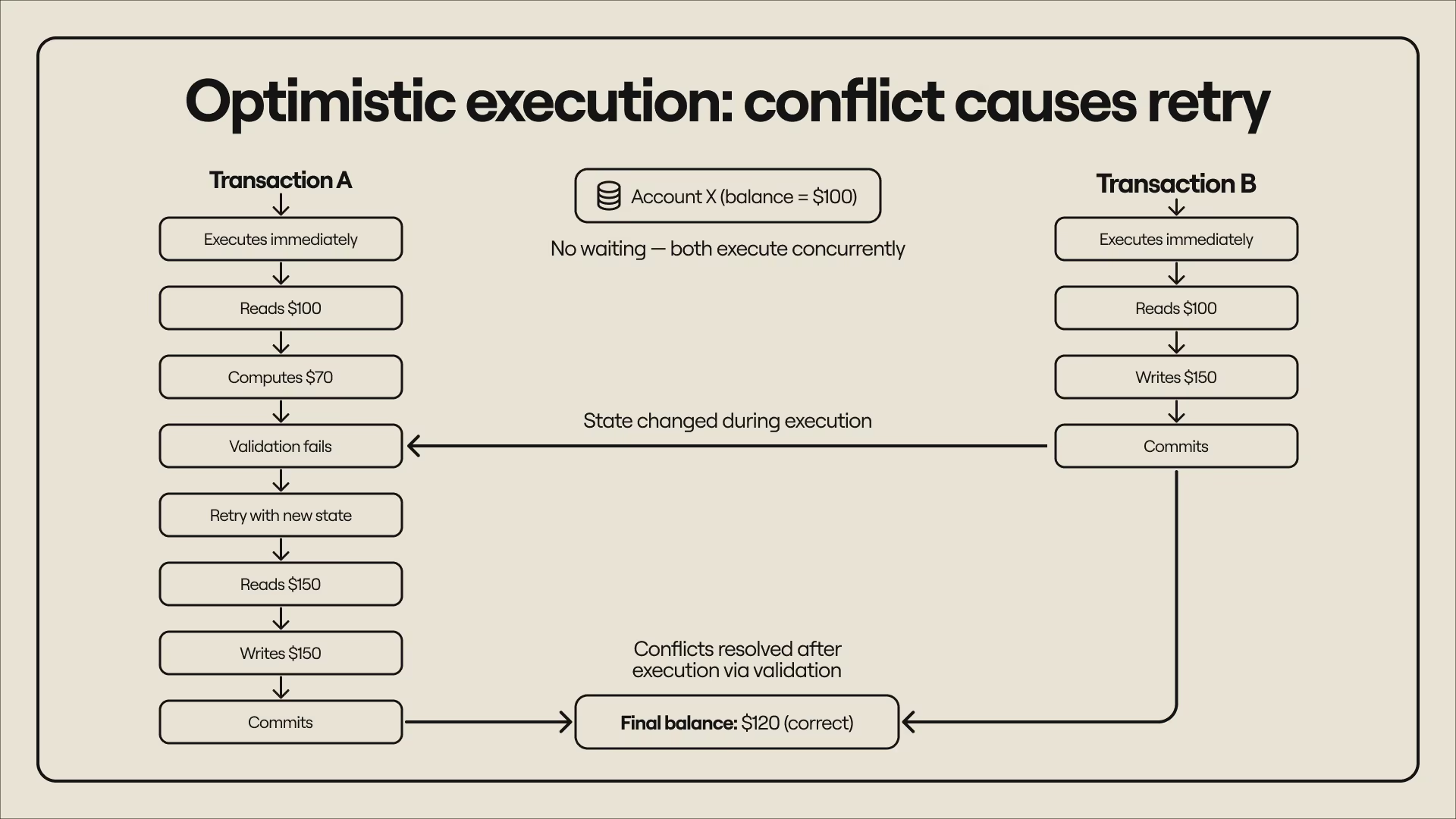

Optimistic execution systems pay the cost after execution in the form of retries–a transaction that reads stale data and produces a conflicting result has to be re-executed with the correct state. Transactions do not declare state access upfront and are always executed concurrently, but the results are validated after execution and rerun if they turn out to be invalid. To use a previous example:

- Transaction A and B both read $100, but the balance reads $150 by the time Transaction A finishes (because Transaction B committed earlier). Transaction A notices the state change has changed, discards the old result, and re-executes with the new balance instead of overwriting it. The final result is $120 because Transaction A calculates $150 - $30 instead of $100 - $30.

- Transaction A and B both read $100, but the balance reads $70 by the time Transaction B is done (because Transaction A committed earlier). Transaction B notices the new state, discards the previous result, and re-executes with the updated balance. The final result is $120 because Transaction B calculates $70 + $50 instead of $100 + $50.

Pessimistic execution and optimistic execution both arrive at the correct result, but use different methods and have distinct tradeoffs. Pessimistic systems assume conflicts are likely and preemptively restrict execution (e.g., delaying transactions) to minimize conflicts. This results in more delays, especially when transactions touch the same state. In the visualization, this shows up as more transactions entering Waiting mode–those transactions remain pending until the system believes it can execute them without conflicts appearing.

Optimistic systems assume conflicts are rare but still validate results after execution to resolve any observed conflicts. This results in more retries, especially when many transactions access the same state. In the visualization, this shows up as more transactions entering Rerunning mode–those transactions have to be rerun because changes in state made their original execution invalid.

Below is a summary of the features of both concurrency control approaches:

Pessimistic execution at a glance

- Transactions declare all accounts that they read and or write before execution starts.

- A transaction that (potentially) conflicts with another transaction must wait for the latter to complete.

- All transactions execute concurrently if no conflicts are observed before execution.

- Some (or all) transactions are executed sequentially if conflicts are observed prior to execution.

- Conflicting transactions are grouped into conflict-free batches. Transactions within a batch execute concurrently, but the batches themselves are executed in a sequence.

Optimistic execution at a glance

- All transactions are always executed in parallel.

- No transaction is delayed.

- No requirements for transactions to declare what accounts they touch during execution

- Transactions commit updates in sequential order.

- Transaction results are validated before commitment–transactions that read stale data are retried.

With the basics of optimistic execution and pessimistic execution fully established, we can now go into how to use the visualization. The next section provides a quick walkthrough and provides concise and useful tips on making the most out of the tool as you explore concurrency control visually.

How to visualize concurrency control in six steps

1. Select an execution mode

Select Optimistic Mode if you want transactions to execute immediately and rerun when they fail validation. Select Pessimistic Mode if you want to minimize conflicts and want transactions to execute correctly on the first try.

2. Customize the workload

a. Use the “Transactions” toggle to adjust the number of transactions (T0, T1, T3…) for each simulation. More transactions increase potential conflicts, especially when a run includes fewer accounts.

b. Use the “Accounts” toggle to adjust the number of accounts (Acc0, Acc1, Acc2…) in each run. Fewer accounts (and more transactions) result in more competition for access to state, especially when a run includes more transactions.

c. Click “Transaction Conflicts” to choose which accounts transactions read or write during execution and adjust the number of conflicting transactions. Adjust transaction access patterns to:

- Create read-heavy workloads (transactions read state more often)

- Create write-heavy workloads (transactions write state more often)

- Create mixed workloads that have read operations and write operations in equal proportions (transactions reading and writing state more often)

3. Modify exclusive access settings

Turning exclusive access ON means any account shared between two transactions will cause a conflict (even for reads). Exclusive Access ON prevents multiple transactions from reading the same account and reduces concurrency, especially in pessimistic mode. Turning exclusive access OFF means multiple transactions can read the same account, but a conflict is registered if both transactions read the same account and write to it during execution. Exclusive Access OFF makes state access less conservative and increases parallelism, especially in read-heavy workloads.

4. Start the simulation

Press Start to run transactions. The transactions (T) orbit the accounts (Acc) in the center. Arrows connect transactions to accounts currently being accessed during execution. Multiple arrows pointing to an account mean more than one transaction is accessing that account, either for a read or write operation.

5. Read the transaction states

Transactions can be in the following states during execution

- Waiting (gray): Transaction is waiting to execute (pessimistic mode)

- Executing (blue): Transaction is executed

- Rerunning (orange): Transaction is being re-executed (optimistic mode)

- Completed (white): Transaction is complete

Here’s an example of a simulation that uses pessimistic mode–notice the various states that transactions occupy during execution:

Here’s an example of a simulation that uses optimistic mode–notice the various states that transactions occupy during execution:

6. Experiment with different scenarios

Press “Reset” to start with a new set of parameters for the simulation. Play with the controls to observe how parallel execution behaves under different conditions with different concurrency control strategies employed. This will give you a good idea of how parallel execution works in a blockchain environment.

Make conflicts more visible–increase transactions, decrease accounts, or add more transactions that touch similar accounts. Or decrease conflicts by reducing transactions, increasing accounts, and removing transactions with overlapping state accesses. Toggle exclusive access mode on and off to see how conservative access affects parallelism. Run the same transaction set in optimistic mode and pessimistic mode to understand the tradeoffs of both approaches.

Conclusion

We didn't build the visualization to show which model is “better”. We did it to show how different parallel execution modes approach concurrency control and solve the problem of preserving the same security guarantees that sequential execution provides. With this article as a guide, you can observe how concurrency control choices lead to different performance patterns and tradeoffs–even as they all achieve the same goal of secure and reliable execution.

If you want an even deeper and more technical understanding of concurrency control, we are preparing a comprehensive deep dive that explores the topic in more depth and illuminates the underlying concepts behind each concurrency control design. For now, you can explore the demo and build familiarity with parallel execution. In the future, we will explore how Rialo uses optimistic execution to provide a high-performance execution environment for applications and guarantee the best possible experience for users.

The dashboard is live at concurrency-control.rialo.io and will remain up for the duration of the demo. Have any questions or need clarification related to the visualizer? Don’t hesitate to reach out. We’d love to help developers build easily on Rialo and are happy to help you understand how to leverage Rialo’s innovative execution approach.

Appendix: What to expect when visualizing concurrency control

This part of the article is for those who want more information on what to expect when running the simulation under different conditions. We’ll go over what you should expect when interacting with the controls and how you should interpret the results you get. This should help you build an intuitive mental model for how concurrency control choices affect execution and UX.

Execution modes

Pessimistic Mode

- Prevents conflicts upfront

- More transactions waiting

- Less wasted computation

In pessimistic mode, you’re likely to see more transactions enter a Waiting state, especially when conflicts are possible. It’s because parallel execution enforces correct results by blocking conflicting transactions before execution.

When transactions are competing for access to the same accounts, pessimistic mode will provide better performance because fewer transactions fail. Conflicting transactions execute sequentially, so transactions never have to be re-executed.

Optimistic Mode

- Allows conflicts to happen

- More transactions retried

- Maximum concurrency

In optimistic mode, you’re likely to see more transactions in a Rerunning state, especially if multiple transactions conflict. It’s because optimistic execution avoids delays (unlike pessimistic execution) but has to enforce correctness by validating transactions after the fact and rerunning conflicting transactions that produce invalid results.

When conflicts are rare, such as when a workload is read-heavy (reads create fewer conflicts) or transactions write separate accounts, optimistic mode performs better because all transactions execute concurrently. Fewer conflicts mean fewer retries, so execution can maximize the advantage of parallelism without wasting computational work.

Exclusive Access settings

Exclusive Access ON

- Shared account access creates conflicts (even reads)

- More transactions wait

- Concurrency reduces

Exclusive Access ON simulates parallel execution environments, particularly those with pessimistic concurrency control, that cannot distinguish between reads and writes. This mode means transactions get exclusive access to an account, no matter what the transaction plans to do.

Consider the previous example (Transaction A and Transaction B updating an account). Now, add a new transaction (Transaction C) that only reads the account without updating it. Logically, Transaction C should be able to execute concurrently because its execution doesn’t conflict with A or B–it can read the account’s balance at any time and still be correct.

But if the scheduler that accepts transactions and schedules them for execution cannot distinguish reads and writes, Transaction C may have to wait, depending on which transaction secures exclusive access to the account and executes first. Transaction C will have to execute in sequential mode, even though it’s only reading a shared account. This reduces performance, especially for read-heavy workloads, because reads, which don’t conflict with writes, are delayed.

Exclusive Access OFF

- Read operations can overlap

- Fewer conflicts and more transactions executed immediately

- Concurrency improves

In this mode, transactions are free to read the same account, and transactions don’t get exclusive access. Using the same example from above, transaction C can execute concurrently with Transaction A and Transaction B and read the account balance. Correctness is guaranteed because Transaction C is read-only and doesn’t update the balance (Transactions A and B both update the balance, which is why they cannot read the balance at the same time).

Turning exclusive access off improves performance, especially in read-heavy workloads. The performance boost is mostly limited to pessimistic mode because optimistic mode doesn’t have a notion of exclusive access and always permits maximum parallel execution and concurrent state access.

Transaction count

Increasing the transaction count means the system must try to process more transactions concurrently, which increases potential conflicts. However, this depends on factors like how transactions interact with accounts, the execution mode used, exclusive access settings, and the number of accounts shared between accounts.

In pessimistic mode

- If transactions access the same accounts or Exclusive Access is ON:

- More sequential execution

- More transactions are in Waiting mode

- If more transactions separate accounts or Exclusive Access is OFF:

- More concurrent execution

- More transactions execute immediately

In optimistic mode

- If conflicts are limited:

- Transactions executed at maximum concurrency

- Fewer transaction retries

- If conflicts are widespread

- Transactions are still executed at maximum concurrency, but more computational work is wasted.

- More transaction retries

No. of accounts

Reducing the number of accounts (while keeping the transaction count constant or higher) means more transactions are forced to access the same state. This can increase conflicts and affect parallelism, but it depends on factors like how transactions access state, what execution mode is used, and exclusive access settings.

1. Low number of accounts + mostly writes

This combination greatly increases conflicts because more write operations overlap between accounts, and writing to the same account always creates a conflict. However, the behavior can slightly change depending on the execution mode:

In pessimistic mode:

- High delays (more transactions in Waiting mode)

- Concurrency is limited (more transactions are executed sequentially, and spare computational resources are utilized less)

- Fewer runs due to few failures

In optimistic mode:

- Low delays (transactions execute immediately)

- More retries (more transactions in Rerunning mode)

- Higher concurrency (maximum parallel execution and greater utilization of computational capacity)

- More computation runs due to more failed transactions

2. Low number of accounts + mostly reads

This combination reduces conflicts in theory because reads are less likely to create a conflict. However, this changes with the execution mode and chosen exclusive access setting.

With Exclusive Access ON:

- Reads block each other

- Transactions are increasingly delayed

- Concurrency reduces

- Pessimistic mode performs slightly worse

With Exclusive Access OFF:

- Read operations overlap

- More transactions run immediately

- Concurrency increases

- Optimistic mode performs well

To summarize: The number of accounts determines how much state is available to transactions, but a smaller set of accounts doesn’t automatically mean more conflicts. That depends on state access patterns, parallel execution modes, and policy on shared reads. The worst-case scenario is the combination of a small number of accounts with many transactions that frequently write new state and/or exclusive access settings. This increases competition for accessing state and forces more sequential execution (pessimistic mode) or more transaction retries (optimistic mode) to preserve safety.

Transaction conflicts

You control which accounts transactions access during execution and how they interact with those accounts by using Transaction Conflicts. It’s possible to create read-heavy workloads and write-heavy workloads (or a mix). These workloads have a different relationship with conflicts and behave differently when combined with varying execution modes and exclusive access settings.

Read-heavy workloads

In a read-heavy workload, more transactions read state (often from the same accounts), and few transactions write state. Running read-heavy workloads with different exclusive access settings and concurrency control policies produces different results.

With Exclusive Access OFF and optimistic mode selected:

- Accounts are read by multiple accounts simultaneously

- Many transactions are processed in parallel

- Very little Waiting or Rerunning

- Maximum utilization of computational resources

- Optimistic mode performs well

With Exclusive Access ON and pessimistic mode selected:

- Accounts are read by one transaction at a time

- More delays during execution

- Limited concurrency and less utilization of computational resources

- Pessimistic mode performs poorly

Write-heavy workloads

In a write-heavy workload, more transactions write state to the same accounts, and a few transactions read state. Write-heavy workloads have different execution patterns when processed with alternative concurrency control techniques.

In pessimistic mode:

- More transactions in Waiting

- Fewer or zero retries

- Limited concurrency, but computation is efficient because fewer transactions are retried

- More transactions executed sequentially

In optimistic mode:

- More transactions in Rerunning

- Higher number of failed transactions

- Computational capacity is utilized more, but likely offset by increased re-execution of failed transactions.

Putting it all together

Reads don’t inherently conflict, except when two transactions reading an account expect to write a new state (read-read operations don’t conflict, but read-write operations do). Read-read operations can, however, conflict when the execution model requires exclusive access for reads (i.e., treating reads and writes equally). Permitting shared reads unlocks opportunities for higher concurrency, particularly for optimistic systems that maximize parallelism. Forcing reads to behave like writes that require exclusive access to an account means simple account checks (like Transaction C from the earlier example) are delayed unnecessarily, and concurrency is reduced.

Writes create conflicts because they invalidate other transactions’ reads and can lead to incorrect results. Pessimistic systems preemptively stall these conflicts by blocking parallel execution of transactions that write to the same shared accounts. Optimistic systems allow conflicts to happen, but fix them later by retrying transactions that fail because of invalid read operations. Both systems achieve correctness and enforce serializability (the property that parallel execution must produce an outcome equivalent to executing a similar set of transactions in sequential order). They just force protocol designers to accept different tradeoffs.