Supermodularity and System Welfare: The Economics of Integration

Supermodularity serves as a guide for determining what is necessary to integrate into a blockchain environment. It is also a lens through which we can understand how correctly integrating complementary components increases system welfare. We define system welfare as the total value created for developers and users after accounting for execution costs, coordination overhead, and operational risk. A blockchain system provides high welfare if valuable onchain activity is cheap, reliable, and scalable, and low welfare if fragmentation, rent extraction, and coordination failures make otherwise valuable transactions uneconomical or unreliable.

Existing blockchains often fail to integrate supermodular components and fragment the stack into multiple layers. After paying the base layer for execution, an application may need to pay fees to other protocols at upper layers of the stack–often for critical services (e.g., oracles and keepers) that are not integrated with native execution. These third-party protocols are usually called “middleware” because they sit in the middle between applications occupying the top layer and blockchains occupying the bottom layer in a typical crypto stack.

Failure to integrate essential features into base layers degrades welfare. Instead of paying a single execution cost to the base layer, applications must also pay fees to middleware protocols that provide services the application needs to function properly, such as oracles, automation, data feeds, privacy, confidential computation, web calls, and bridging. These fees quickly compound over time, because each provider sets prices independently and is motivated to maximize profit on each transaction (even if it makes overall execution more costly and affects demand).

The result is a less-than-ideal situation in which execution becomes extremely expensive (because service providers keep raising prices in isolation) and applications raise user fees to run profitably. This subsequently pushes out price-sensitive users, reducing total demand and destroying surplus value. Value is lost because once users stop making transactions, applications make less revenue and pay less to service providers, who (ironically) make less profit than before.

.png)

Expensive transaction fees are not the only welfare-related problem created by fragmenting the blockchain stack. Middleware providers do not provide the same guarantees of availability, censorship resistance, and decentralization as the base layer. Having to stitch together multiple middleware services when building protocols (e.g., a DeFi application might need a bridge, an oracle, a price feed, and a privacy gadget) increases operational risk for developers, as these components are more likely to go offline, censor transactions, suffer exploits, and generally undermine the decentralization guarantees that blockchain applications are supposed to enjoy.

Supermodularity is the correct move for a blockchain that deliberately optimizes for maximum welfare. By selectively integrating critical primitives–like oracles, automation, data feeds, privacy gadgets, confidential computation, and interoperability–into the base layer, it’s possible to fix fragmentation, rent extraction, and coordination failures that degrade welfare for participants in a blockchain ecosystem. Concentrating control of critical functions into one entity (the chain itself) trades off some decentralization for greater coordination and alignment in the pricing and delivery of execution and execution-adjacent services.

Without integration, blockchains suffer from compound marginalization. “Compound marginalization” is a formal name for the problem we introduced earlier: multiple service providers at different levels of the blockchain supply chain charging high prices to maximize margins (an issue that worsens when providers have monopoly power) and unintentionally shrinking demand and destroying surplus value by making execution uneconomical for applications and their users. Solving compound marginalization requires coordinating price-setting, which is hard to do when each provider has an incentive to maximize its own profit.

Fortunately, we have an economic solution: vertical integration. When a manufacturer notices that external control of a complementary stage of the production process (e.g., producing a critical input) is increasing production costs, reducing reliability, and creating negative value, it can decide to vertically integrate that function and bring it in-house. This usually leads to more reliability, higher value, increased output, and, more importantly, lower prices for consumers–the latter being a result of concentrating incentives and price-setting power in one entity (instead of two).

Our previous article on supermodularity showed an example: an electric vehicle manufacturer integrating battery production to optimize production costs, stabilize supply chains, and increase overall product quality. In particular, the carmaker can reduce the price of the final good (electric vehicles) because it controls the pricing of a critical input (batteries), and its production process is now oriented toward increasing total demand rather than merely extracting higher margins. Reducing prices (counterintuitively) leads to higher margins because cheap products stimulate demand–as demand scales, the manufacturer can reduce unit production costs and make more profits overall.

.png)

Vertical integration of complementary production components is the core insight of supermodularity. Instead of outsourcing services that complement execution, a blockchain can integrate them into the core protocol as native primitives. In Rialo’s case, integrating critical functions rather than outsourcing to external providers reduces execution costs by eliminating the need for applications to pay extra fees to monopolistic service providers controlling different layers of the blockchain stack. The cost of accessing execution-adjacent services (like oracles, automation, data feeds, privacy gadgets, and confidential computation) is now absorbed into a single, coherent cost paid to the base layer for execution.

Those extra services don’t automatically become free, but the chain has monopoly pricing power and can offer them at a lower price. The chain still has an incentive to increase revenue; however, it also needs to stimulate demand for execution (more onchain activity = more fees = more revenue). Keeping prices of system-critical primitives stable incentivizes developers to build more functionally richer applications, which users are encouraged to use because transaction fees are set at a reasonable rate.

Supermodularity also makes it easier to reason about the reliability and availability of critical services. In a blockchain like Rialo, execution is enhanced by the base layer’s decentralization–users know that they can depend on the chain to execute valid transactions and expect this function to be reliable, efficient, and secure at all times. Integrating critical functions with execution means users now have the same guarantees as base-layer execution: services will continuously operate reliably, securely, and efficiently as long as the chain remains reliable, secure, and efficient.

It is important to clarify that this doesn’t mean a blockchain should integrate everything. Integration only provides value when it involves the right components and functions–components that are strategically complementary and jointly improve a system’s capabilities and output. The various examples we have put forward all satisfy this key requirement.

This is where supermodularity becomes essential. It provides a rigorous framework for assessing which components complement each other in production and, when tightly integrated, create emergent system-level properties. This prevents a protocol like Rialo from overintegrating and suffering from unnecessary bloat. If integrating a particular component won’t increase total output, value, and efficiency, or if it doesn’t complement other components in production, it is outsourced to external providers and treated as a commodity input.

.png)

How fragmentation destroys surplus in practice

The welfare costs described in the previous section are real and borne by developers and users today. As explained previously, those costs result from fragmenting the blockchain stack into separate layers and forcing applications to rely on (monopolistic) middleware protocols for access to critical services that complement execution. Reliance on third-party infrastructure increases execution costs, degrades availability, and lowers aggregate demand.

Currently, developer surveys show that protocol teams are spending hundreds of thousands of dollars per month to integrate their applications with offchain infrastructure (oracles, keepers, bridges, privacy gadgets, confidential computation, and more). The problem is particularly pronounced in high-throughput chains, where third-party infrastructure costs are higher, and protocols must contend with increased operational overhead.

The loss of welfare that occurs when the blockchain stack fragments into a patchwork of middleware and third-party vendors can be pretty significant. For context, the same developer surveys estimate that middleware fees can wipe out more than 90% of the transaction value for certain operations. This is a classic case of welfare being degraded by unnecessary fragmentation and by existing chains failing to integrate valuable primitives.

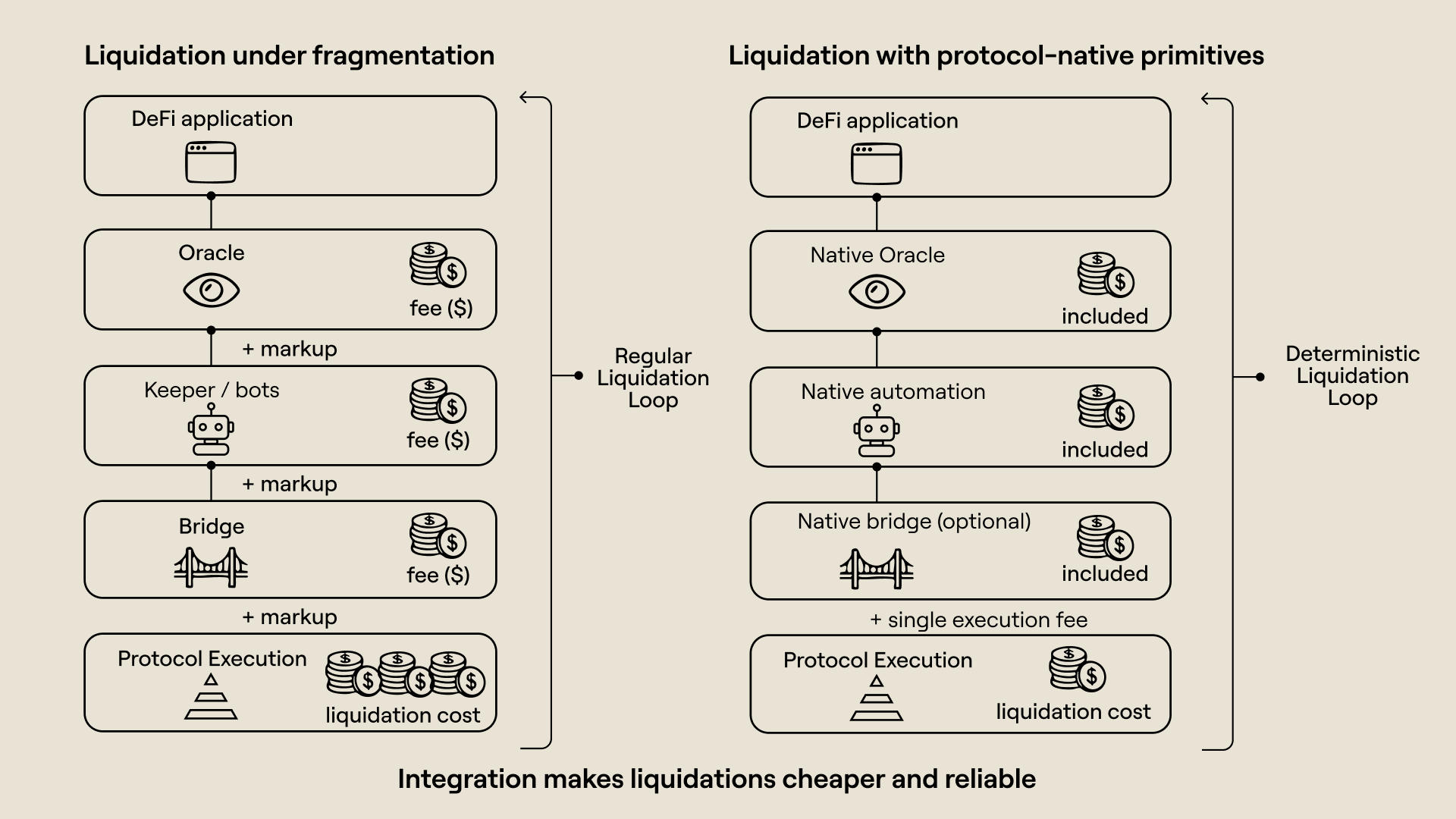

Let’s illustrate the problem better by considering a scenario where an application needs to liquidate a loan and must coordinate with several providers during the process:

- Oracles (providing new prices)

- Keepers (monitoring prices and liquidating undercollateralized loans)

- Bridges (in case cross-chain execution and settlement are necessary)

Each service provider must be compensated separately, whether through a direct fee or a revenue-sharing agreement (e.g., a keeper might receive a share of the profit from a liquidated loan). If each provider has monopoly power, it can charge even more for its services. At some point, the total execution cost will approach or exceed the value created by the liquidation transaction.

When this happens, protocols can either raise fees for users or throttle liquidation frequency. Both are bad for users: higher fees directly discourage usage, while delaying liquidations increases the risk of insolvency (the system cannot stop the accumulation of bad debt) and could lead to losses for users who provide loans. No one wants their money to disappear, so it’s only rational that users exit the system if it cannot manage risk reliably.

The net effect is that total demand falls, onchain activity stalls, and surplus value is destroyed–a situation reminiscent of the economic concept of “deadweight loss”. Deadweight loss is the value lost to the economy because valuable transactions that would be beneficial do not occur due to market distortions, such as monopolies and excessive taxes. In this case, service providers operating as monopolies and charging high prices raise total execution costs and force users to make fewer transactions.

.png)

This results in users earning less, protocols earning less, and service providers earning less. Everyone loses because fragmented pricing and coordination failures prevent transactions that could yield valuable economic activity. This is a consequence of how blockchains have been traditionally designed for years, often outsourcing critical functions to external providers to satisfy vague architectural ideologies like “modularity”, or failing to integrate supermodular components despite self-describing as “integrated” or “monolithic” chains.

The old modular and monolithic framing fails to provide an economic theory of integration and cannot guarantee the maximum welfare for participants in a blockchain ecosystem. Supermodularity, however, approaches integration from an economic perspective and uses integration as a tool to improve welfare-related outcomes for developers, users, and the chain as a whole.

As a truly integrated chain, Rialo exerts significant control over the execution stack–handling both execution and functions that reinforce execution–and orients it around user adoption, developer activity, higher system throughput, and long-term value accrual. It avoids deadweight loss by coordinating the pricing of services that applications need and subjecting users and developers to a single set of incentives.

We can explore how an integrated chain like Rialo can boost welfare and spur economic activity by reusing the earlier example: liquidating loans. Rialo’s supermodular infrastructure enables automated, recurring workflows that can also integrate with external data (such as oracle-provided prices). This enables closed-loop financial systems that operate seamlessly and autonomously, with no extra handling required.

With Rialo, the previous liquidation loop now looks like this:

- Price information supplied from protocol-native oracles (create an automated transaction that either triggers the oracle pull prices at intervals)

- Loan positions continuously monitored by native automation (set a transaction that recalculates LTV ratios for open borrowing positions at intervals or whenever oracle prices change)

- Undercollateralized loans automatically liquidated by the chain when collateral value is negative (set up the protocol to emit an event when the loan position falls below a threshold and create a reactive transaction that responds to the emitted event and automatically liquidates the loan)

In this scenario, execution, oracles, and automation are integrated and delivered by the chain. The liquidation loop still costs money (computational resources are not free), but the redundant markups disappear, and the incentives are better aligned. This leads to lower prices per transaction for liquidation operations, so developers don’t have to raise prices, and users get access at prices they can afford. Surplus value also increases–users make more transactions, applications earn more revenue, and the chain enjoys higher throughput, adoption, and revenue.

This (again) shows integration can produce significant economic payoff when implemented with supermodularity in mind. By integrating primitives and functions that complement each other in production and result in meaningful changes to a system’s capacity and functionality, supermodular chains like Rialo are better equipped to eliminate rent extraction, stabilize execution costs, and align incentives with the needs of developers and users. The outcome is a higher level of welfare enjoyed by participants in a chain’s ecosystem.

Conclusion

Supermodularity turns blockchain design into an economic problem rather than treating it as a choice between competing architectural ideologies. Instead of merely asking whether a chain should be monolithic or modular, we ask which components complement each other in production and unlock higher output, value, and, more importantly, welfare when integrated into a single system.

Combining execution with other critical primitives that complement execution–native oracles, native web calls, native automation, confidential computation, and native bridging–makes execution more valuable, reliable, and powerful. More importantly, removing additional layers of fees from the blockchain stack and absorbing them into a unified price charged on execution reduces the cost of interacting with the chain and running applications profitably and sustainably.

In a world where throughput, speed, and basic composability are increasingly commoditized, blockchains will start differentiating based on how well their components work together (compositional power). Supermodularity enables Rialo to maximize coordination across components and integrate supermodular primitives in ways that compound economic efficiency, raise total output, and improve welfare in the long term.