How Rialo Secures Prediction Markets

Prediction markets are where information becomes money. They allow people to trade on the likelihood of future events–anything from election outcomes and sports results to geopolitical milestones and technological breakthroughs. Since accurate predictions earn rewards, participants are incentivized to act on what they know. Someone with private knowledge (e.g., an insider at a tech company or a geopolitical expert) has a good reason to express that knowledge by taking a market position.

This design enables prediction markets to aggregate independent fragments of information (such as rumors, intuitions, anecdotal knowledge, and expertise) into a collective signal about what’s true or likely to become true. A well-designed prediction market operates as a decentralized truth engine capable of beating even expert forecasts and polls at predicting the future and calibrating the probability of specific outcomes.

However, every prediction market needs a trusted mechanism to determine “what really happened” to function properly. The blockchain cannot observe the real world a smart contract cannot read the Associated Press’s website to know election outcomes, watch a Fed meeting to get the latest interest rate decision, or scan social media for product announcements. To settle predictions, the prediction market needs an oracle to report these facts. Oracles bridge blockchains and real-world systems, importing off-chain information for onchain applications to use.

Oracles make prediction markets possible. However, they (re)introduce the need for trust (contra blockchains’ goal of enabling trustlessness). The blockchain cannot verify the information an oracle provides; if the oracle lies, the blockchain will accept that lie as truth. A malicious oracle can provide false information, trigger incorrect payouts, and destroy confidence in the entire market.

The risk scales with market size. As prediction markets grow and payouts scale up, the incentives to manipulate them also increase. At some point, bribing or compromising the oracle becomes economically rational. This brings up a fundamental question: “How do you secure a prediction market when the incentive to lie about reality is great?”

Mechanism designers have proposed different types of oracles to address this tension. Some rely on economic deterrence–making dishonesty prohibitively expensive. Others rely on cryptography–using secure hardware, like TEEs (trusted execution environments) to make dishonesty technically impossible. Some combine both. To understand why this distinction matters, we need to first map out how prediction markets actually get their data.

How prediction markets get data

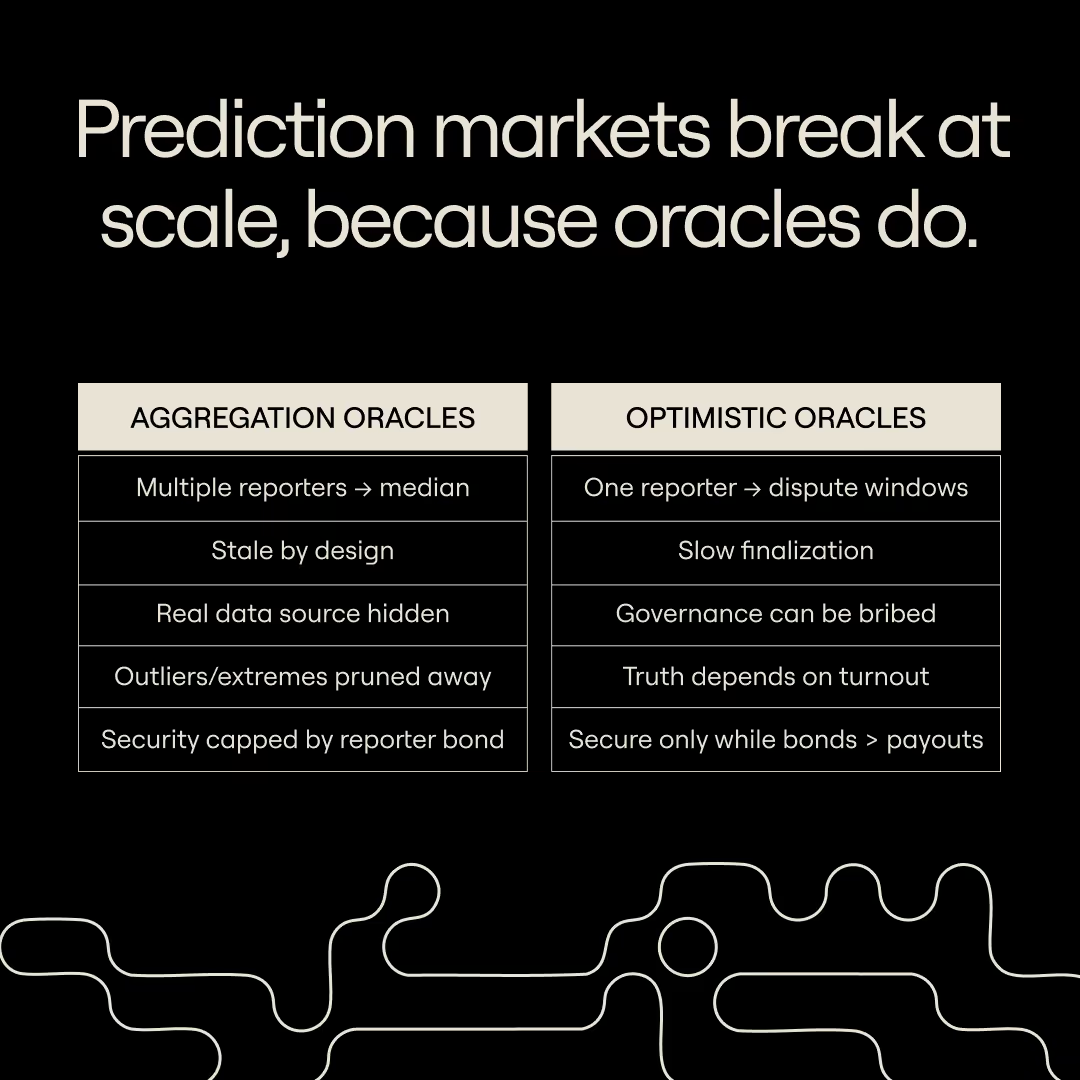

To understand how prediction markets source truth, let’s explore the two dominant oracle architectures: aggregation oracles and optimistic oracles.

Aggregation oracles

An aggregation oracle uses a distributed trust model involving multiple reporters to improve resilience and accuracy. Each participant submits a value, and the oracle aggregates them–using a mean, median, or majority vote–to determine the final result. Reporters are typically bonded to ensure honesty and sanctioned for actions deemed to be misbehavior. Compared to a single-party report oracle, aggregated oracles are more resistant to censorship (more people can report) and harder to compromise (attackers must bribe a quorum rather than a single reporter). However, they are an imperfect solution in several respects:

- Transparency. The quorum of reporters acts as a middleman between the chain and a data source (or set of sources). The source itself is not naturally available to the chain.

- Single-source homogeneity. Because the security model of decentralized oracles uses a group consensus, incentives heavily favor the quorum (all relying on the same source). This is the data equivalent of groupthink.

- Staleness. Because of the “groupthink” incentives inherent in the security model, the quorum of reporters will logically converge on the stalest (honest) value in the quorum. For time sensitive values, reporting a fresh value that is unavailable to others risks slashing or penalization.

- Data loss. Many metrics, such as mean, can be heavily skewed by outliers reported by a single member of the quorum. As a result, values which appear “extreme” in some way are pruned or “aggregated away” via a metric like a median. This is useful to guard against oracle attacks, but it also means losing the most valuable information– cases where the value is moving quickly, and so the true value can be extreme.

- Proof of Stake redundancy. The security model of decentralized off-chain oracles uses a consensus-like convergence on a value with bonded stake, slashable on misbehavior. This essentially duplicates the structure of a proof-of-stake chain’s security model without adding anything new.

- Security that doesn’t scale. The oracle security provided by bonding and slashing will penalize misbehavior up to the value of the bond. But this bond must secure against any and all rewards for misreporting, which may come from, e.g., the total market size of the prediction markets. If the bond is 100k, and the quorum can misreport a value to collect $1m from a prediction market, it may be worth it.

Optimistic oracles

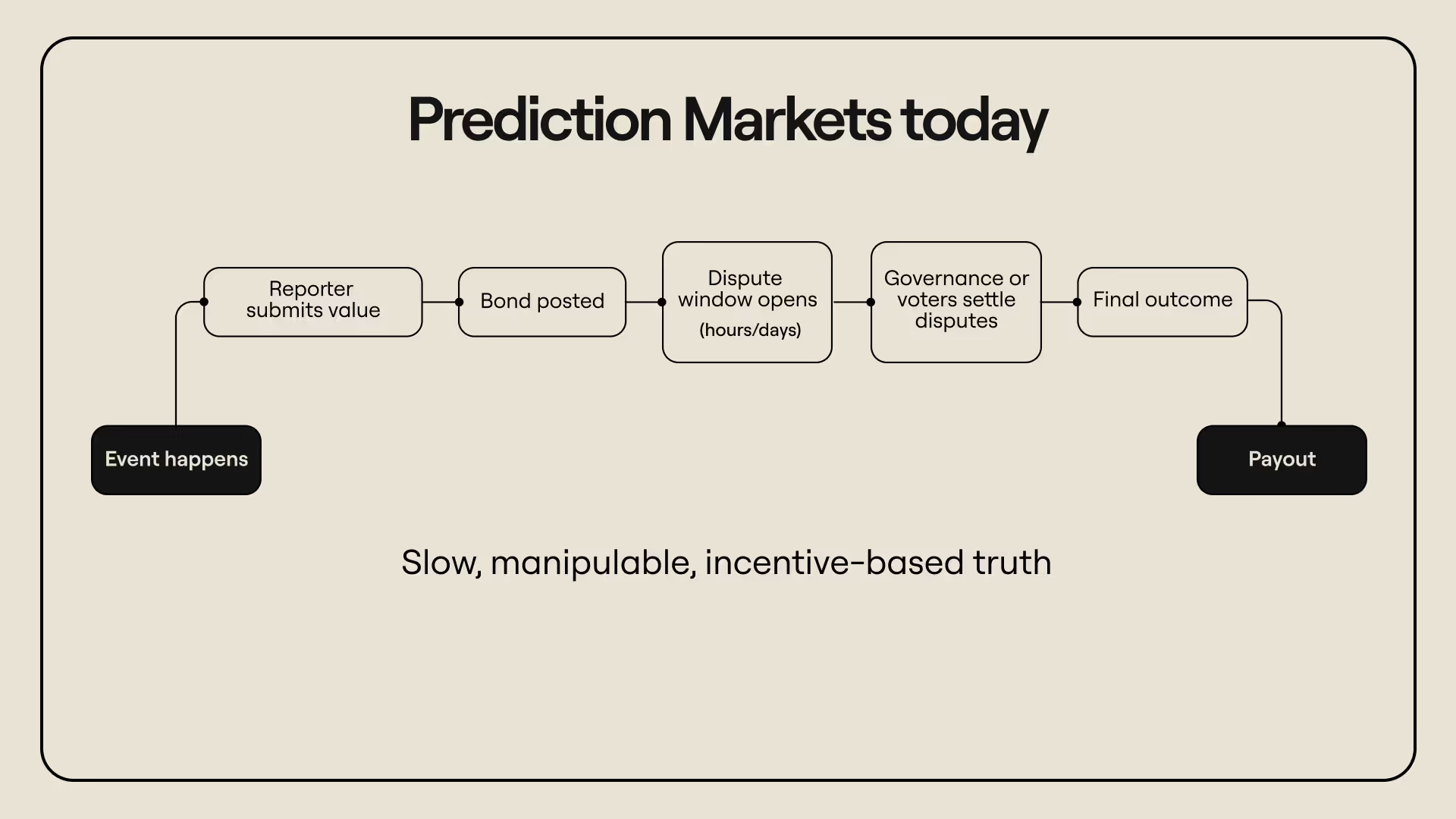

Optimistic oracles assume reporters are honest by default and punish dishonesty after the fact. Anyone can report information if they put up a bond, after which a challenge window opens. During the challenge window, others can dispute the submission after posting their own bond (bond requirements for challengers discourage spam challenges that could stall the system). If no one challenges the submission, it becomes final; if someone successfully challenges, the original reporter loses their bond (part of it goes to the challenger while the rest is burned).

This mechanism keeps the system decentralized and efficient. It also aligns the incentives around truth: honesty is the default option because lying is costly. However, the underlying security assumption–that rational actors will always dispute lies and defend the truth–can break down as markets grow large and payout potential increases. This essentially introduces a “who watches the watchmen” problem by pushing the ultimate source of truth further upstream. Optimistic oracles function only when there is another trusted source of information to reconcile disputes.

Suppose the protocol requires a governance vote to settle disputes. An attacker could bribe token holders to abstain from voting, quietly acquire governance tokens to sway the result, or launch a series of low-cost challenges to exhaust honest participants (remember: honest challengers must post a bond before disputing submissions) before submitting a final false report. Each of these attacks is feasible so long as the expected payoff from manipulating the market outweighs the downside.

The optimistic model makes truth conditional on incentives–it endures only as long as honesty remains the economically rational choice. When market incentives flip, the oracle’s optimism becomes a liability. We’ll explore what this looks like in the next section.

Modeling oracle failures

Imagine a fictional protocol called Prophecy Markets: a decentralized prediction platform that lets users trade on real-world events. Prophecy uses an optimistic oracle and allows anyone to propose an outcome by posting a bond. The system opens a one-day dispute window for other participants to challenge the submission; if no one objects, the result is finalized, and payouts are executed.

Consider a market on Prophecy–“Will Candidate A win the state election?”–with $10 million in volume. Alice, a savvy trader, notices flaws in the incentive design and sets out to manipulate the market for her own benefit.

First, she bribes the designated reporter to submit the wrong outcome–claiming Candidate A won when Candidate B actually did. The false submission triggers a dispute, but governance must now step in to resolve it. Unfortunately for Prophecy, governance participation is thin. Token holders are apathetic, and a few key whales can be bribed to abstain or even vote dishonestly (she can also buy tokens from holders to swing the outcome). With enough votes secured, Alice’s side wins.

At this point, the contract accepts a false result as canonical truth. Alice earns a huge payout from the manipulated market. But she’s not done yet. Knowing that the market’s reputation will tank once people discover the lie, she opens a short position on Prophecy’s governance token. When public confidence collapses, the token price crashes–giving her another windfall.

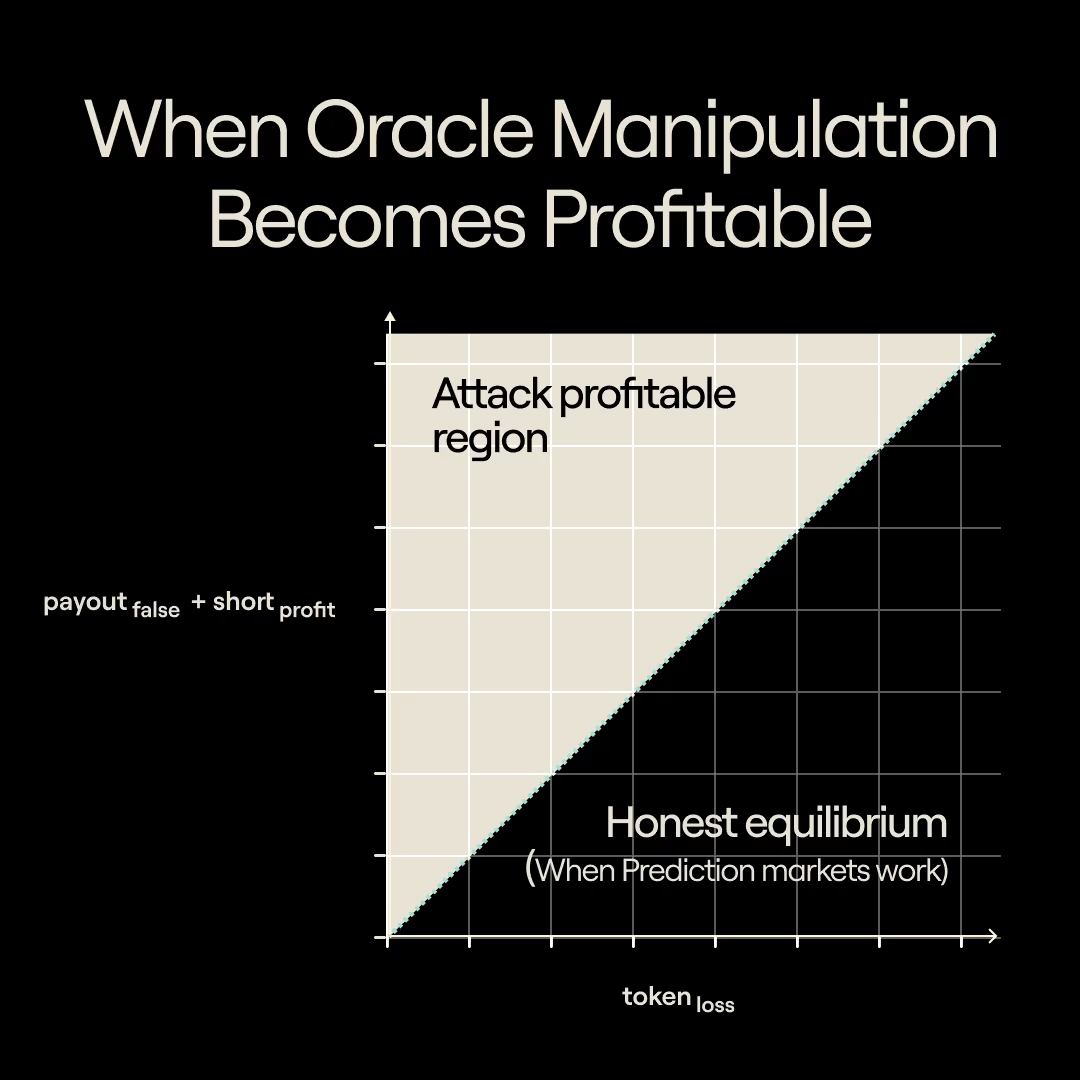

This incident illustrates a general pattern. In every incentive-based oracle, there exists a region where the expected payout from lying exceeds the expected cost of being caught. Once the system’s total value crosses that threshold, honesty ceases to be a Nash equilibrium. The deterrent bond is no longer binding because the expected return on dishonesty is positive.

We can express this condition informally as: (payout from false outcomes + short profit) > (token loss from crash)

For an attacker like Alice, the potential profit comes from two sources: the manipulated market payouts and the gains from shorting governance tokens (either of the oracle or the prediction market). The losses mainly come from the devaluation of any tokens the attacker holds after the truth emerges. Bribes and coordination costs are secondary; an attacker can often buy tokens directly from disinterested holders rather than paying them to vote (they can also buy tokens on the open market).

This balance defines the economic security boundary: Below the boundary, honesty is stable (lying costs more than it pays); above it, deception becomes the rational equilibrium. When a market’s total value approaches or surpasses this boundary, the system is susceptible to failure.

A formal model of prediction market security

A prediction market’s security (and resistance to attack) is influenced by three major factors:

- Payout potential: How much an attacker gains by manipulating outcomes

- Short profit: How much an attacker gains from the governance token’s collapse in value

- Token loss: How much money an attacker loses by holding the same token they just destabilized

An attack becomes profitable when the combined gains from (1) and (2) exceed the expected losses from (3). This can be expressed in pseudo-mathematical notation as:

This relationship defines the economic boundary. Below the boundary, it is unprofitable to attack the system. Above it, acting dishonestly and manipulating the system is the economically rational move.

A simulated example

Assume Prophecy’s governance token has a market capitalization of $500 million. The protocol hosts ten active markets, each averaging $10 million in trading volume. Suppose an attacker can extract 10% of each market’s volume if they falsify outcomes, and the governance token typically drops 30% following an integrity failure.

Now, imagine an attacker holds 5% of all tokens in circulation (enough to propose and influence votes) and shorts another 10% of the supply via exchanges. If they falsify all ten markets, their potential profit is: (10 markets × $10M × 0.10) + ($500M × 0.30 × 0.10). That’s $10 M + $15M = $25 M in combined gains.

Meanwhile, their loss from holding the token post-crash is: $500 M × 0.05 × 0.30 = $7.5M. Even after accounting for token loss, the attacker walks away with $17.5M in profit. The system is “attackable” because the combined payout and short profit exceed the token loss.

Testing the model

To visualize how this dynamic behaves under different conditions, we can express it programmatically. The code below (adapted from our simulator prototype) computes whether a specific configuration of parameters makes a prediction market secure or attackable.

def decision_logic_millions(market_cap_m, n_markets, extract_per_market_m, short_notional_m, turnout_frac, crash_frac):

# attack profitability test

payouts = n_markets * extract_per_market_m

short_profit = short_notional_m * crash_frac

token_loss = market_cap_m * turnout_frac * crash_frac

attackable = (payouts + short_profit) > token_loss

return {

"attackable": attackable,

"attacker_hold_frac": turnout_frac

}

Here are plaintext explanations of key parameters from the snippet:

- market_cap_m: Total market capitalization of the governance token (in millions)

- n_markets: Number of markets that can be attacked

- extract_per_market_m: Average value extractable per market

- short_notional_m: Size of the attacker’s short position

- turnout_frac: The fraction of total token holders likely to participate in dispute resolution (proxy for vigilance)

- crash_frac: Expected decline in token price if the attack is discovered

Let’s run the model with the following parameters:

- market_cap_m = 500 ($500M)

- n_markets = 10

- extract_per_market_m = 10 ($10M)

- short_notational_m = 50

- turnout_frac = 0.2 (20%)

- crash_frac = 0.3 (30%)

We compute:

- Payouts: 10 x 10 = $100M

- Short profit: 50 x 0.3 = $15M

- Token loss: 500 x 0.2 x 0.3 = $30M

- Total gain: $115M > $30M (system is attackable)

Even with a moderate turnout (20%), the attacker still profits from the attack. To restore security, Prophecy would need far higher governance participation (> 75%) or larger bonds, both of which are impractical in real-world contexts.

The simulated examples capture the fragility of most optimistic oracles’ security models and show how these systems become unstable beyond certain economic thresholds. To solve this problem, we need an approach to designing oracles for prediction markets that provides stronger guarantees of correctness and embeds greater incentives for honest behavior.

Why Rialo is different: direct, verifiable resolution from primary sources

We’ve shown the conditions under which holders of a prediction market voting token would find it rational to rug the market, but would NFL.com lie about who won the Super Bowl? That’s the model offered by Rialo: the market’s resolution is a line of code that can point to a source on the web, and trustlessly report the results. For a championship market, that might be nfl.com; for rates, federalreserve.gov; for climate, weather.com or ipcc.ch.

This design offers three benefits:

- Real‑world reputation does the heavy lifting. These institutions already secure their credibility with their business models. When reporting the winner, the rate decision, or the dataset correctly is standard business for them, then the report itself is a positive externality for prediction markets supported by Rialo.

- Decentralized Resolution. If prediction markets on the championship, interest rate, and weather all align simultaneously, we’ll see how that affects exploitation incentives for token vote resolutions. While it’s not literally a zero probability event that the Federal Reserve lies about the interest rate to rug a prediction market, it becomes even less likely to imagine they’re coordinating with weather.com and NFL.com to all do so at the same time. Thus, even if the prediction market chooses the wrong resolution source, failure in one domain does not cascade across unrelated domains.

- Eliminating the middleman game of “Telephone”. Every oracle gets its information from somewhere. Rialo makes that “somewhere” explicit and machine‑readable. Anyone can inspect, simulate, and independently verify the exact source and policy—at lower cost than maintaining a separate voting or reporting layer.

Compared to aggregation oracles, Rialo changes the shape of risk and quality:

- Full source, not a median. On Rialo, it’s possible to return the full underlying data stream (e.g., a feed from a named publisher), not a median that prunes outliers. Apps can compute medians, averages, or custom transforms on top—without losing the “extremes” that often matter most.

- Fresher by construction. Aggregated staking systems converge on the safest stale value to avoid slashing. Rialo reads primary sources as they publish, making timeliness a feature of the source itself rather than a consensus game.

- No redundant staking layer. Rialo doesn’t duplicate a proof‑of‑stake security model at the oracle level. Resolution pointers and results are finalized by the chain itself; there’s no extra bonded reporter quorum to maintain.

- Higher effective security at scale. To manufacture a false outcome, an attacker would need to corrupt multiple independent, highly visible institutions (or censor them in concert). On Rialo, an MCP design mitigates censorship at the routing layer, and protocol stake provides economies of scale: as usage grows, the cost of attacking the chain‑anchored resolution path rises while the marginal cost of honest resolution falls.

Net effect: Rialo makes “truth sourcing” concrete, auditable, and purpose‑built for prediction markets. Instead of asking whether a token vote can be bribed across many markets at once, app developers choosing a resolution ask a simpler, domain‑specific question: how likely is this primary source to misstate its own facts, and for how long? That reframes oracle security from a correlated governance risk into a set of independent, verifiable ties to the public record—programmable in one line of code.